A PASSAGE OF AN ARTIST

THRU TIME AND SPACE

by Popoy Castañeda

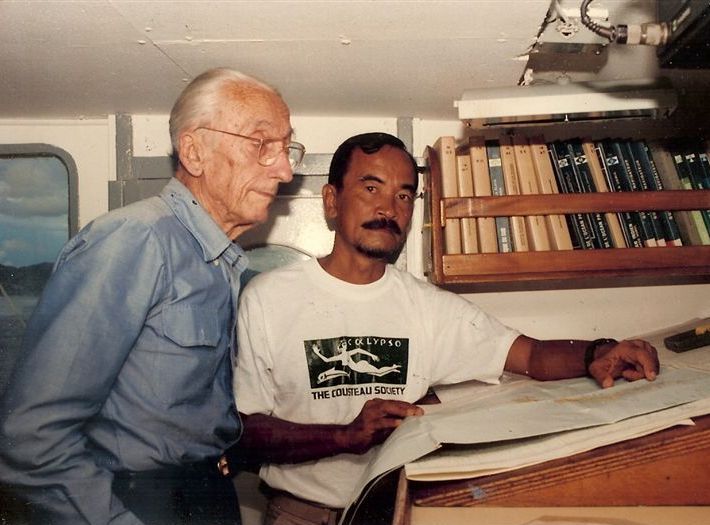

Popoy, the diver and guide, and the legendary Jacques-Yves Costeau study Palawan's hydrographic chart.

[See: A Betan's Journey Thru Time and Space, in Memoirs & Reminiscences]

Part 2 -

World War II Life in Palanyag and Manila

At daybreak when the curfew was lifted we departed for Lola Juana's farm in

Barrio Talon, Las Piñas. At that time Manila was connected to the southern provinces by only

1 road, the National South Road. Everybody going south passed through it if you

were going to

Cavite; or western Batangas, you would go past the Zapote Junction, cross the Zapote bridge and

then you

were in the province of Cavite. If you were going to Laguna, Quezon and Eastern Batangas

you would turn left, take the left branch of the road and in a short while you

were in Barrio

Talon. Lola Juana’s farm was along the Highway and so was the farmhouse. It was full daylight when we

reached the farmhouse. Surprisingly it was not the nipa hut we were expecting but a 2-story

wood and concrete structure painted yellow with a balcony. (I could still see the

farmhouse way back in 1955 on my way to UPLB prior to the opening of the South Highway

(now the

SLEX).

The scenery then was a far cry from today. Palanyag then was rural

or

semirural and people from Palanyag had a peculiar singsong accent. I was always laughed at

by my cousins from Gagalangin. Even today we still retain that accent when we talk

with each other. So going south along the South Road (in Parañaque the South Road now is

Quirino Avenue) past the San Dionisio Chapel there were almost no houses there till

you reached the site of the cockpit which marked Las Piñas Poblacion. You go past the Bamboo Organ

church, Parish of St. Joseph, on your right and approximately 5 to 7 houses on the same

side was the residence of the Tiongkiaos, Lola Juana's family. (The Tiongkiaos are half

Chinese Mestizo Sangley so is Eriberta Tomas, Lola Tina’s and Kapitan Tinoy’s mother, who is

registered on the church baptismal registry of the Cathedral Parish of St. Andrew as “Mestiza

Sangley", half Chinese.

The caretaker-tenant (his name I think is Mang Eksekiel) met us and with Tio

Tabing supervising we unloaded our stuff and billeting was soon assigned. Tio Tabing

and the men started filling out sandbags for the rice granary on the groundfloor designated

as our air raid shelter. Tio Rasing had the old family radio installed (surprisingly there

was electricity on the houses along the South Road). Tio Jose was busy inspecting the

vegetables cultivated or growing wild around the farmhouse. Lola Tina soon had the

caretaker pounding newly harvested palay for our lunch and by then we were soon settled in

our new surroundings.

There in Talon that evening I saw for the first time fireflies swarming around an Aratiles tree lighting the tree like a Christmas tree. I had seen fireflies before and my father, when he was able to capture one, would put it in a small bottle for me. But this was more dramatic because it was a swarm of the insects. The second time I saw see this sight would be at Donsol, Sorsogon 75 years or so later. Tio Jose the following day made paper balls and the following night he caught and put the fireflies inside and Kuya Nil and I had lighted up paper lanterns. Life was so quiet in Talon and if not for the reports of Tio Rasing who tuned in on the short wave broadcast on our radio at night you would think we were on a vacation. Several days or weeks had past when one early morning we were told by Lola Tina to keep watch for Lolo Camilo who was coming with news from home. Near lunchtime Tio Jose sighted a familiar figure emerging from a bamboo grove from the north and soon they met Lolo Camilo, who had walked all the way from Palanyag. He had bad news that the Japanese forces had landed in northern Luzon and at Lamon Bay, Quezon province and the Japanese would surely take the South Road on their way to capture Manila. So we evacuated back to Parañaque where Auntie Pining advised us to join them. W we made a dash for Angono, Rizal where Auntie Pining and her husband Tio Irot (Cornelio Santos) knew families there. On the way we joined up with some families from La Huerta and with them we occupied a school building just outside the población.

Soon we learned that Manila was declared an "Open City" but there was still fighting at the outskirts of Manila. And so it was decided to move in the población in the house of Auntie Pinings’s friend, a Mrs. Villaluz, whose house was in front of the Angono Catholic Church. We stayed in Angono Poblacion for a period I cannot remember, until we decided to move again this time. Since Manila was declared an Open City and under the Japanese control, we all moved in with Auntie Pining, Tio Irot and Tio Irot's daughter Tessie and son Honesto in Singalong. We stayed with them for a while but then my father was summoned by his mom, my Lola Loleng (Dolores Hilario Castañeda), to go and take us to stay with them in Gagalangin since Lolo Atsang (Deogracias Castañeda, Sr.) was very sick. So against my wish I had to join my Tatay, Nanay and Lito and stay in the intersuelo (mezzanine) of the Castañedas house at Gagalangin.

We were accompanied to Gagalangin by Tio Tabing, Tio Rasing and Kuya Nil.

There at Gagalangin I was acquainted with my grandfather Lolo Atsang who was dying of an infection of his respiratory system he contracted while a

prisoner of war of the U.S. in Guam. Lolo Atsang of the Castañeda clan of Imus, Cavite

was a military courier of the Magdalo faction of the Katipunan under Emilio Aguinaldo. Barely a week

after Aguinaldo was captured in Palanan, Isabela, Lolo Atsang who was 14 years

old was captured and together with the other prisoners of war in Guam he was now dying of

asthma. I also got

acquainted with my cousins Letty, Carina and Cora (still a baby). I never was at

the Castañeda home in Gagalangin on Calle Juan Luna nor any place in the city. It was a 2-story structure on a 250 square

meters plot of land, with a backyard and a small garden in front. Compared to my play area in

Palanyag this was a prison. Across the street was the public school building occupied by the

Kempetai, the dreaded Military Police of the Japanese Imperial Forces. All children were not

allowed to open the front windows or play on the front yard because my grandmother and

aunts feared to attract the attention of the Japanese. However every time my brother Lito,

then a toddler, always attracted the attention of the Japanese who sometimes played with him when

Ate Telly, sister of Kuya Erning, who came to live with us to be Lito’s yaya, took him across

the street in the morning. Lito at that age was fair skinned and chinky eyed. There came a time

when a young English speaking Kempetai officer would cross the street and play with him

and even give him bananas. Every time this happened my Lola Loleng broke out in her

Spanish prayers. Living at the house I had to be contented with playing

alone using my imagination enriched by comics collected for me by Tatay - Tarzan, Prince

Valiant, Flash Gordon and Superman. At times Tatay would tell me stories about his paintings

especially when he was working on a historical piece like when he painted Magellan's burial.

I learned about the discovery of the Philippines from my father, but even then I always pestered my father about going back home to Palanyag. So about a month had gone since we arrived at Gagalangin when he told me he was taking me to Palanyag. We left after an early lunch and a very long goodbye with my mom, Lolo Atsang who seemed to be on the mend, we took a calesa to Divisoria, then a tramvia (street car) to Quiapo Church, where Ka Nena and Pina Nery (they were very familiar to me), Auntie Auring’s friends, had a stall of hand-embroidered clothes beside the Carriedo gate of the Quiapo Church. Tatay left me with them and in the afternoon Lolo Camilo with his calesa came to take Ka Nena, Ka Pina and me back to Palanyag. The day after I returned to Palanyag, Tio Tabing, Tio Racing, Kuya Nil and I went to the beach to dig for Parros, the blue clams, Lola Juana’s and Tina’s favorite, which could only be found in the part of the beach where St. Paul College was at present. Then it was the campus of the St. Andrew’s Parochial School and that part of the beach was bordered on the school side with tall almost tree height Aroma bushes. There Kuya Nil and I went to dig for Surf clams “Halamis”. Tio Tabing with Tio Rasing went to a group of young men who were waiting most of whom I recognized frequenting the halo-halo shop of Ka Trining across the street. Some were barkadas of Tio Tabing and Tio Rasing and frequently practiced ballroom dancing on our sala with the piano playing of Kuya Nil. Later my uncles joined us in digging for clams with them going into the deeper part of the water to dig for the Blue Clams. It did not take me long to be back in rhythm with life in Palanyag - the pace of life, the sounds, the church bells waking you up in the morning and the singsong accent of the people permeating your daily existence. But most of all when we went to the beach I never realized how much I missed the sea, the sight, the sound of the surf and the smell.

However just a few days in my stay my father was back to fetch me home with the sad news. Deogracias Castañeda, Sr., my grandfather, joined his Maker early last night. Lolo Camilo made a special trip and took us to Gagalangin where my grandfather’s wake was. After the burial of my lolo my father took me back to Palanyag. By this time Auntie Auring had started a store on the ground floor beneath the corner bedroom. It was a cooperative store where members could use scripts to buy cigarettes, rice, sugar, corn and other basic needs. Outside by the M.H. del Pilar window was a papag (a bamboo bench as wide as a bed) where people could sit down while waiting to be served or exchange pleasantries with townmates who were usually around. The activities at the store kept everybody busy and that gave me more liberty which extended my range which by this time included learning to swim and dive for oysters and paddle a boat. I would eventually extend my range to the saltbeds and fishponds across the river and the fruit orchards were mangos, ripe duhats, sweet atis and guavas were for the taking as long as you could outrun the irate owners. I also became more assertive since I now knew how to use my fists to settle arguments and I belonged to a group the boys of San Nicolas Chapel. The frequency of my spanking proportionately increased. My punishments were administered by Lola Tina with a bamboo fence slat 2’’ wide and 18‘’ long supplied by the fence of Lauro Leonardo’s (Tata Uro) whose fence was conveniently at hand every time I needed a whipping. I never resented the punishments thanks to Tio Tabing. He always told me to accept the whippings as payment for the privilege of wandering out to the salt beds, swimming in the river or fistfights with other boys.

I knew Lola Tina was so scared of me drowning or running into trouble. One morning when we were sitting down for breakfast one of Tio Rasing’s friends came running shouting - "Run!", "Hide!" The Japanese had closed the bridge and were rounding up the men. Tio Tabing and Tio Rasing calmly and swiftly disappeared but Tio Jose was out to the market. Unknown to me they had a previous warnings from the other communities about the ‘’Sona”, the tactic of the Japanese of rounding all males in the church where they were interrogated. In just a few minutes the Japanese were on M.H. del Pilar Street we could see the soldiers with rifles with bayonets. Leading them was a Japanese man in white short sleeved shirt and khaki pants with a Katana, a Kempetai officer. Behind the Japanese was a larger group guarded by Japanese soldiers with fixed bayonets and when they came nearer we could recognize them and among them was Tio Jose with his hands tied behind him like the rest of the group. Lola Juana and Lola Tina were crying. The group passed the house and Tio Jose signaled with a nod and a smile that he was okay. We soon found out that the prisoners were taken to the church. We spent a very sleepless night but when morning came and the lifting of curfew, Tio Jose along with most of the men of La Huerta were released. Allmost all but for a few who were brought to Fort Santiago, the infamous dungeon built by the Spanish conquistadores now used by the Japanese as an interrogation center. Tio Jose named the people taken. All I could remember was Dr Cile who was detained at the fort for almost a month and retained the physical scars to his dying day. Tio Jose was lucky because apparently at that time he was already doing work for the guerillas along with his 2 brothers. He gained the Japanese gratitude that night when he was able to relieve 2 Japanese officers with their toothaches. However he had stories of the interrogations and water tortures employed by the Kempetai. Tio Tabing and Tio Rasing came home later that night. They apparently took shelter and hid out in the fruit orchard of Ka Sotera Nery across the river.

By middle of the week everything seemed to have returned to normal

except for the talk about the men who were taken to Fort Santiago. I returned to my

concerns exploring the mangrove patches along the river banks, improving my swimming

skills learning how to dive and using the homemade diving googles and the use of a

boat. I did all of these against Lola Tina’s cardinal rule of not going to the river. As I honed

my skills my whipping became more frequent, but that was the rule of the game. I became known

by the elder people of the area as the “apo ni Maestrang Gustina”. The people of La Huerta went on with their lives trying their best to live their

lives normal as they could. The fiesta of San Nicolas de Tolentino was celebrated with a mass

at the chapel, and a procession complete with a brass band finished to wit an impromptu sarsuela

and an amateur singing contest on the stage built across the M.H. del Pilar-San Nicolas

Street junction. When May came there was the Flores de Mayo. Just before the final

procession I noticed the absence of Tio Tabing and Tio Rasing. When I asked for them no one

answered. I was warned under threat of the bamboo fence slats not to talk about them.

We went on our activities of living despite the the difficulties imposed by the

war. Food especially rice had to be rationed. Some poor families would learn to eat only

twice a day. Some resorted to eating corn and camote and some not eat at all. Medicine became

scarce if not unavailable. Tio Jose became busier in the community since he now functioned

as a doctor for the community giving advice on simple medical matters as diarrhea,

stomach aches in addition to dental problems. One morning I overslept and when Auntie Auring tried to get me up she felt that

I had a temperature and I complained about my throat which felt raspy and very itchy. Tio

Jose looked at my throat and said it was red and so he gave me a throat swab but the

next morning my fever was higher and my throat was painful and swollen and so it was assumed I had the mumps and was given the standard treatment of indigo based

plasters. But by the 4th day my throat was so swollen and I had mucus coming out of my

throat when I coughed so they called Dr. Cile who was just released by the Japanese and

still recuperating from his ordeals. He came immediately and he found out I had diptheria and I

needed sulfa drugs. My father was summoned from Gagalangin while the whole town scrounged around for sulfataihsol.

He went with Tio Jose to his uncles in Imus, Cavite but

still no medicine and was told that the guerillas in the vicinity of Maragondon might

have some since they were known to be supplied by the Americans. Leaving Tatay at Imus, Tio

Jose braved the Japanese checkpoints and overzealous guerillas, walked to the

wilderness of Maragondon, Cavite where a guerilla unit was operating and armed with a letter

from Colonel Mariano Castañeda got several sulfa drugs.

In the meantime in Palanyag I was getting worse. Ninong Augusto, Nanay's brother, came with Aurita but all that they could do was pray. They said that I was already delirious and practically on death's door when Tio Jose and Tatay arrived with the sulfa drug which was quickly administered by Dr.Cile. By the next morning after the administration of the drugs my fever was low and I was on my way to recovery. A week later I was strong enough so Tatay took me back to Gagalangin. At Gagalangin I gradually flowed in the life of the Castañedas where I stayed mostly in my father's studio watching him paint, helping him in cleaning his brushes, and painting his canvas with the prepared ground and sandpapering the stretcher frames. About a month later I asked Tatay to bring me back to Palanyag. This time at the Quiapo Church store Auntie Auring was there and this time we had a new carretela to take us home with Ka Teban Cruz also from La Huerta. Before we boarded the caretella, Auntie Auring bounded my arm with bandages after putting some folded paper envelopes inside like splints. And when we stopped at the first Japanese checkpoint, I was cuddled by Auntie Auring and pretended I was sick so we didn’t have to go down and be searched. (Later after the war they told me we were carrying messages for the guerillas). Auntie Auring and I with Ka Teban made several such trips for the guerillas. (I only knew of this after the war). Then one or two weeks after, Tio Jose came with news that the U.S. Army had landed at Leyte and in anticipation of fighting Tio Jose decided to go with Tio Pedring whose wife Tiya Tinay was from Imus. I was excited but by the next day my father who got the same news from his uncle from Imus took me home.

In a few days the news seem to have been forgotten and that morning we were having breakfast of cassava flour pancakes upstairs with our Lola Loleng. While waiting for our pancakes my cousin Letty noted that there were a lot of airplanes flying around which attracted our attention. Somebody said they were on training, but then we heard the sound of machine gunfires and then we saw several airplanes on fire plummeting down. Then we saw the insignas on the planes doing the shooting, the big star of the US Air Force, but suddenly the air battle shifted overhead and bombs and shells were falling near. We all made a dash downstairs where we took shelter under our mezzanine bedroom and with Lola Loleng’s prayers stayed in our air raid shelter till late afternoon. The air raids soon came regularly in the morning and we were told that those were done by planes flying out of aircraft carrier. After a week of this daily air raids we soon got used to it and as a routine we would eat a very early breakfast, then proceeded to the air raid now provided with mats, cushions and pillows. The bombings went on for about 11 days and one afternoon we were sitting down for an early dinner when we heard the staccato of automatic gunfire. We ran to the window and saw that the Kempitai HQ had already been vacated and from the north coming from the direction of Caloocan we saw tanks and infantrymen in green fatigues being greeted by people. Then we saw the lead tank with an American flag. They had returned.

ONLINE PHOTOS

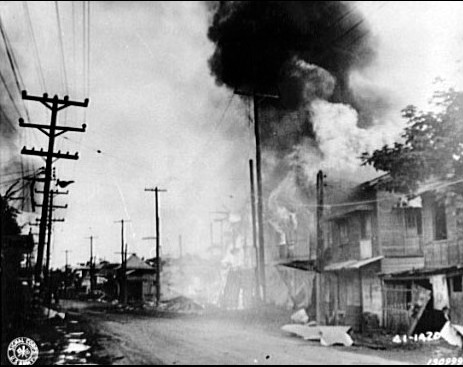

"A burning building along Taft Ave. which was hit during the

Japanese air raid in Parañaque, December 13, 1941"

"Japanese at Parañaque Bridge"

(To be continued)

Links:

o Part 1 - My Life in La Huerta

Back ---> Memoirs & Reminiscenses)