Bataan and the Death March as Seen by Some Filipino

Veterans

by Conrado (Sluggo) Rigor, Jr., UPD'60

The recently released article ("A

double dose of hell: The Bataan Death March and what came next") by CNN’s

Brad Lendon and reprinted in the Philippine Post drew attention and revived

opinions expressed by Filipino soldiers when they were still around as well as

surviving and aging veterans of the Pacific War.

A war history buff and a veteran’s son, I wish to add a few inputs to the

interesting episode about Bataan and the Death March. I am thankful that there

are recorders of wartime stories in the Philippines which many of our fathers

had hoped that a legacy of patriotism, courage and gallantry are enshrined in

our history as a freedom-loving people.

My own father passed away early at 46 but had been active as secretary general

of the Veterans Federation of the Philippines (VFP). As a young reservist

officer, he had led a battalion in the final battle that ended the Pacific War

in the Philippines. I have had numerous opportunities, as an advocate of aging

soldiers in Manila and in Seattle, to meet and speak to my father’s

comrades-in-arms. They all spoke profoundly about their aspiration to leave a

legacy to younger generations. Allow me to narrate briefly.

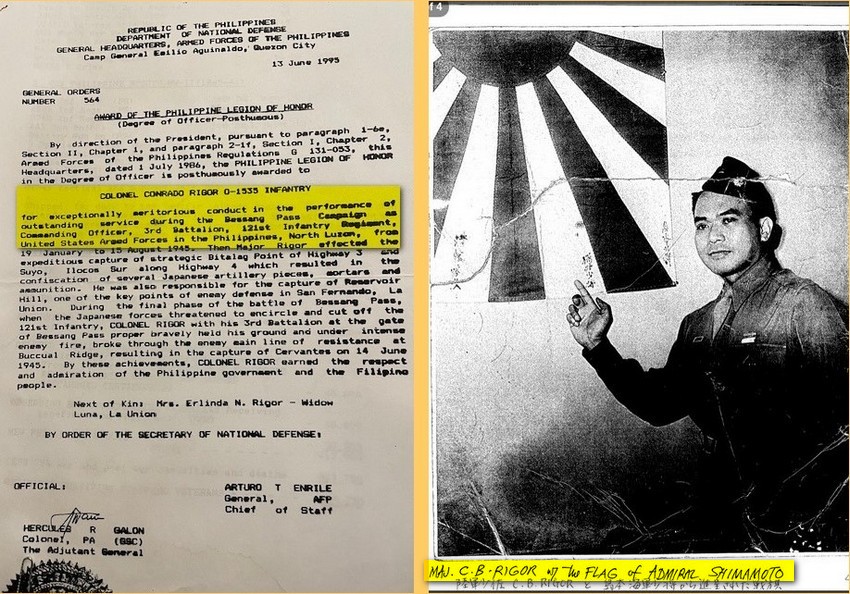

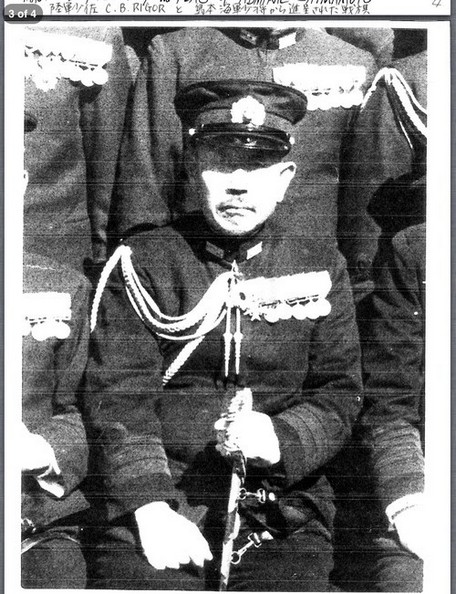

Vice Admiral Kyoguro

Shimamoto led the submarine sneak

attack on Pearl Harbor. He surrendered with Gen.

Yamashita

to Filipino soldiers at the battle of Bessang Pass.

Filipino veterans of that war have ironically tagged Bataan, Corregidor and the

Death March as “ignominious defeats,” a term used by a prominent military

officer-turned-political leader. (My family keeps and treasures a clear MP-3

audio recording of a eulogy this leader had delivered in May, 1960). Filipino

soldiers of the U.S. Commonwealth Army in WWII have lamented the fact that these

infamous wartime events have become more prominently known, creating a sad

impression of weakness of the Filipino’s military capability in war. They

collectively pray that a serious assessment and true accounting to balance such

tales of subjugation be undertaken by today’s historians, critics and

journalists.

In the celebrated book written by the USAFEE-North Luzon Commander Col. Russel

Volkmann, “We Remained,” he had paid uncommon tribute to the Filipino warrior as

“among the world’s finest.” He had focused on the northern Luzon front where

4,800 troops and top Japanese officers led by the feared Tiger of Malaya,

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, surrendered together with Vice Admiral Kyoguro

Shimamoto who had led the triumphant submarine sneak attack on Pearl Harbor

years earlier.

Indeed, shouldn’t it be time for military historians to focus on the glorious

triumphs of the Filipino soldier in the Pacific War? And to place Bataan and

Corregidor side-by-side with victorious battles like Bessang Pass, the rescue

from the Cabanatuan Concentration Camp of 600 American and Canadian POWs by

Filipino soldiers, and the Filipino’s brave underground guerilla operations?

Together with some colleagues, we have endeavored over the years, as a charter

member of the Sons & Daughters of the Defenders of Bataan & Corregidor, to raise

funds for a 2-year professorial chair in University of the Philippines’

Department of History and the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

The academic project that we envision will support an academic research and

study to respond to the query: “How and What Precisely Was the Role of the

Filipino Soldier in Helping Win the Pacific War?”

We believe this is a key issue that has remained unanswered since the end of the

war. It is a fact that WWII was fought at the height of racial discrimination in

America so that After-Battle Reports in the Philippines, as Filipino military

historians have noted, were mostly, if not all, written by U.S. soldiers. To the

silent consternation of Filipino officers and men, this reportedly resulted in

minimizing the role of Filipino soldiers. It is also an underplayed and

hardly-known fact that the highest ranking Japanese officer in the Philippines,

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, led 4,800 of his men in a bloody retreat rampaging

through Manila, central and northern Luzon. In a three-month last stand,

Yamashita was cornered and had surrendered with high-ranking Japanese officers

to soldiers of a USAFIP-NL Filipino battalion in a fierce three-month long final

battle at Bessang Pass in the rugged Cordillera mountain ranges. It was in this

largely unknown, unheralded engagement, war veterans proudly relate, where the

last shots in the Pacific War were fired. It was in this battle that gallant

Filipino soldiers “wrapped themselves in glory,” as one surviving battalion

commander shared.

This battle, in the homeland and even here in the US, has never been afforded

enough attention. University of the Philippines historian-educator and WWII

specialist of Asian Studies, Prof. Rico Jose, has researched extensively on

various stages of the war with emphasis on the roles played by American,

Filipino and Japanese forces. He and his late historian-educator wife had

traveled several times to Japan to do in-depth research and validation of

accounts about the invasion, occupation and eventual surrender of the invaders

in the Philippines.

These largely unknown facts about WWII military history are important to us Army

Brats because it was our fathers who carried the brunt in defending the country

against invaders, a lesson that we feel is vital for patriotism to be sustained.