A Son’s Story

Fate whispered to the warrior:

“You cannot withstand the storm…”

The warrior whispered back:

“I am the storm.”

-Author unknown

My father’s contemporaries tell me he was an

authentic war hero---with emphasis on the word ‘authentic.’ Of course this makes

the family genuinely and silently proud. Being a war history buff, I often

wonder why there are lesser stories told about victories featuring Filipino

soldiers during the last world war. Were they not key players who belonged to

the triumphant Allied Forces of World War II in the Pacific? Except for the

overplayed MacArthur U-turn to the archipelago, military historians seem to

focus more on defeats and infamy like Bataan, Corregidor, and the Death March.

We commemorate these woeful events of subjugation every year but rarely remember

those where the Filipino soldier had dutifully helped defeat the enemy.

In one crucial and bloody military operation in the

final months of World War II, my father had led three all-Filipino battalions of

the 121st Infantry, USAFIP-NL. Reinforced by gritty bolomen from the Mountain

Province, they assaulted Bessang Pass in the rugged mountains of North Luzon. It

was Dad’s unit that broke through a formidable enemy defense line entrenched

within the mountainous terrain of the Cordilleras. That hard-fought battle that

lasted several months led to the surrender of the feared Tiger of Malaya,

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, and other high-ranking Japanese Imperial Army and

Naval flag officers who had regrouped in the Philippines from nearby Asian

cities. They had hoped that with the fabled Tiger in command, they could create

a formidable stand. Among them was a ranking Admiral, the Vice-Chief of Staff of

the Japanese Imperial Navy, who had helped maneuver the submarine attack on

Pearl Harbor in 1941.

My father, “Daddy” to us his nine children and to our

mother Erlinda, was not much of a talker. He was the silent,

self-effacing-to-a-fault type. In close circles of friends, he was known as an

upright, ram-rod-honest soldier-scholar, a poet, writer, and an ROTC reservist

from the University of the Philippines. Close friends and associates called him

“CB” or Condring. In his writings, he had paid homage to poets E.E. Cummings and

Jose Garcia Villa when he studied philosophy and letters as a government scholar

at the Columbia U in New York following his wartime service. He took up courses

there with the then General Dwight (Ike) Eisenhower. After a three-year stint in

the U.S., he returned to the Philippines to help establish the English

Department of what is now a national institution, the Philippine Military

Academy (PMA) in Loakan, Baguio.

Throughout his forty-six abbreviated years on this

planet, he rarely spoke about his wartime exploits. But his comrades-in-arms had

recognized his dedication to the cause of the veterans when he was unanimously

chosen to be the first secretary general of what is now the Veterans Federation

of the Philippines (VFP), an organization that he had helped to organize so that

there would be advocacy and substance to the peacetime campaigns of the

forgotten Filipino soldier.

His comrades-in-arms (who later became distinguished

personages) like Fred Ruiz Castro, Macario Peralta, Carmelo Z. Barbero, Pilar

Normandy, Ernesto Rodriguez Jr., Francisco Bautista, Roberto Reyes, Eulogio

Balao, Simeon Valdez, Cris De Vera, Jose Crisol, Nicanor Jimenez, Jose Banzon,

Arnulfo Banez, Amador Daguio, Pio Escobar…to name a few… Dad’s peers who would

frequent the quarters where the family had lived at various military camps. They

would recount what he had accomplished that fateful day in June of 1944 when the

rising morning sun was hidden by clouds in the rugged ridges of Bessang Pass.

What Dad had dubbed in his post-war writings as “The

Battle of the Clouds” is said to have marked the official end of hostilities in

the Philippines after General Yamashita and his staff were escorted down the

foot trails of the Cordilleras to Camp Spencer in La Union. From there the

legendary Japanese General was taken to Manila for his celebrated military trial

and eventual execution as a war criminal in Los Banos, Laguna.

Dad, in his journal writings, pointed to the battle

in Bessang Pass as an “engagement of redemption,” coming full circle after “the

shame and ignominy that was Bataan.” His colorful lines about the battle at

Bessang would later be used rather extensively by then Senator Ferdinand Marcos

when he campaigned for the highest office of the land in 1966. A wordsmith at

heart, Daddy had unwittingly laid out through his after-battle reports and

writings a clear path for the ambitious Senator Marcos to tread. The politician

from Ilocos Norte and his apple-polishers created in the process the impression

that the dreaded General Yamashita had personally surrendered to him---when in

reality he was safely tucked away as staff in an obscure military personnel

office. He had supposedly feigned sickness 85 kilometers away from the site of

the bloody battle. Asked by one of Dad’s officers why he was not in the

frontlines that day, the then Maj. Marcos, who was in bed at Camp Spencer’s

dispensary, replied wryly, “I am not in the mood for heroics.”

Barely twenty-three years later, after stints as a

congressman of Ilocos Norte and later as a senator, Ferdinand Marcos would

create a controversy because of a film story and campaign line, “For every tear,

a victory,” lines so utterly familiar to what Dad had written about the triumph

at Bessang Pass. Shortly after Dad suddenly died in May of 1960 at the age of 46

due to asthma complications (and because of incompetence of medical staffers at

the V. Luna Medical Center in Quezon City), his writings, files, records and

journals vanished. According to my mother, she had turned them over to some of

Dad’s comrades-in-arms to be used in recording the USAPIP-NL’s role in World War

II. As if the trauma of Dad’s passing away was not enough to his still-in-shock

family, a devastating storm and flood two weeks after he was laid to rest nearly

washed away the brand new home that he had lovingly built in Little Baguio, San

Juan. Wet, torn and muddied, all of his library books, records, journals and

files were damaged beyond repair. Whatever remained in his library about “The

Battle of the Clouds” were most likely lost forever. Only in the writings,

recollections and testimonies of those who had fought with him would remain.

Only the tamper-free World War II files of the United States military would now

reflect the names and the recorded roles of Filipino fighting men in the

benighted peninsula of Bataan, the rock-like defense that was Corregidor, the

infamy of the Death March and then the shining valor, redemption and gallantry

that was Bessang Pass. But many still wonder to this day if envy and prejudice

that lurked in the hearts of those who had recorded and revisited historic

military episodes would diminish the glory of the Filipino soldiers and

guerillas who fought a war that was hardly theirs.

The book written by a communications officer and dear

friend of Daddy, Ernesto Rodriguez Jr. (founder and first president of the

College Editors’ Guild (CEG), a prestigious organization of young Filipino

academics) entitled “The Bad Guerillas of Northern Luzon,” is considered by

historians as a factual and priceless chronicle of the complicated military

campaign in that region during the war. The book recounts the day-to-day pursuit

of Yamashita’s retreating army by Filipino soldiers who were under the

telegraphic command of Col. Russel Volkmann of the United States Armed Forces in

the Philippines-North Luzon (USAFIP-NL). The desperate Japanese Imperial Army

had ravaged Manila and parts of Central Luzon as they retreated northward.

In a rare storytelling episode on our way to Dolores,

Abra one summer vacation in the early 50s, when we kids were still in grades

school, Dad parked the car on a roadside and pointed to the mountain ranges in

the distance where he had fought side-by-side with brave Filipino soldiers as

they pursued well-entrenched Japanese forces. He said that many of those who

were fighting against his troops were young Korean boys not more than 15 years

old. Frightened, hungry and sick, the young Koreans were prisoners of war (POWs)

who were forced by Yamashita to wear ill-fitting combat uniforms and to fight

the Filipinos. Many of them ran from their battle trenches to surrender to Dad’s

men. #

Epilogue

About two decades after Dad was buried at

the Libingan ng Mga Bayani in Fort Bonifacio, I met several of his old

comrades-in-arms who had fought side-by-side with him in Bessang Pass. Each one

had expressed dismay over an epic battle that could have been the most profound

glory hour of the Filipino soldier in WW II if it were ever made public. The

surrender of the highest-ranking, most feared Japanese Imperial Army General to

a gritty battalion of Filipino military officers supported only by a band of

barefoot and spunky Ilocano Bolomen from the provinces of Abra, Ilocos Sur and

the Mountain Province was all but forgotten. Why? Because the American officers

behind the battle lines—far away in La Union----upon learning of the

breakthrough against Yamasita’s almost-impregnable defense lines by the

USAPI-NL’s 121st Bn. were in disbelief. They ordered the Filipino detachment at

Bessang Pass “not to announce anything until further orders.” Two days later,

only after the Americans had arrived in Bessang Pass, that the announcement of

Yamashita’s surrender was bannered to the whole world. Even today, Dad’s aging

comrades can only shake their heads in silent anger. One outspoken Filipino

officer commented: “Well…the ‘I Shall Return’ PR blitzkrieg and full-bore

propaganda campaign had to have a glorious spin to it and Bessang Pass was a

sure fit.” (The other surprising spin to the historic surrender of the Tiger of

Malaya was that he reportedly refused to emerge from his cave in Bessang unless

there were American officers to receive him---for fear that the Filipinos would

kill him right there. This was pure rubbish, Dad and his comrades would declare.

For his war crimes, Yamashita was summarily executed by the Americans in Los

Banos anyway.) And so, countless Filipino warriors remain unheralded, forgotten

and buried under the WWII radar screen of valor and sacrifice. So like that

haunting song of patriotic servitude, Dad and his gallant comrades “…will never

die, they’ll just fade away…” Burning in the hearts of warriors who fought for

freedom and who revere truth is a conviction that redemption always comes in the

end game. #

Conrado (Sluggo) Rigor, Jr. / UPD60 / Seattle, WA /

Summer 2004

About the Author

Conrado N. Rigor, Jr. is executive director of a

non-profit human services organization (www.idicseniorcenter.org) based in

Seattle. Sluggo is a community journalist who also served as information attache in

Seattle’s Philippine Consulate General in the late 1980s. He is the eldest son

of a WWII veteran who had figured in the historic Battle of Bessang Pass where

General Yamashita and his invaders finally surrendered to end the Pacific War.

His email:

sluggorigor@gmail.com.

===============================================================================================================================================================================================================

Dear Brod Norms,

I hope you are able to download items here.

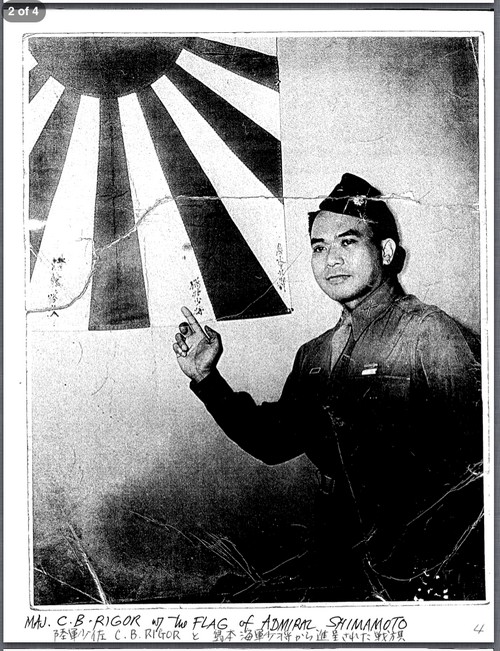

My Dad posing before the historic flag that was surrendered to him by Admiral Kyoguro Shimamoto who led the sneak attack of submarines on Pearl Harbor.

The flag flew on Admiral Shimamoto's lead submarine after a successful mission on US ships. The

Admiral later surrendered at Bessang Pass together with the feared Tiger of

Malaysia, General Tomoyuki Yamashita. It was my Dad's unit, the USAFIL-NL 121st

Inf., 3rd Btln., reinforced by gritty bolomen from the Mountain Province, that

scaled the backwall of the Pass. Yamashita, a brilliant military strategist, had

dug into Bessang Pass as the enemy's last stand in the Philippines.

I tried contacting his family in Osaka to try to return the flag that is now in

my family's possession.

Sluggo, 9/06/18

Picture 1 - Then Maj. C.B. Rigor points to the flag of Japanese Admiral Shimamoto.

Picture 2 - Admiral Kyoguro Shimamoto led the

submarine sneak attack on Pearl Harbor and later surrendered his flagship's

symbol to Maj. C.B. Rigor after the decisive Battle of Bessang Pass. This final and last major engagement lasted for five

months and led to the capture of the infamous Tiger of Malaya, General Tomoyuki

Yamashita, following the breakthrough of the once-impregnable enemy defenses by

the all-Filipino 3rd Batln., 121st Infantry of the USAFIP-North Luzon.

Picture 3 -The family of Admiral Shimamoto now living

in Osaka, Japan. On the wheelchair is the Admiral's 81-year old son and the lady

is a granddaughter. (We, the Rigors, connected with the family after a year-long

search to ask if they wanted the flag returned to them. What followed next is

another post-war story of human interest).

===============================================================================================================================================================================================================

Postscript, by Norman Bituin

1) As I told Sluggo, the Rigor house in Little Baguio, San Juan is close to the hearts (and butts!!) of the UPD'65 Black Saints being the site of our 1st and 3rd sessions. On our first session, on the white t-shirt we wore was written in pentel pen a number based on our last names alphabetically. I remember my number was "23" (Bituin). Near me was number "25" (Cabanatan). Elmor Villanueva said he was number "120". We finished with 29 new brods, the Black Saints, on Dec. 9, 1965.

2) I did some research on Bessang Pass on the internet. The United States Army concluded as "fraudulent" and "absurd" Ferdinand Marcos' claims on his war stories. The Filipino soldiers from the Third Battalion of the 121st Infantry, USAFIP-NL, were led by the real hero, Maj. Conrado Rigor, Sr., to whom Admiral Shimamoto surrendered the Japanese flag. If interested, see links below.

https://memebuster.net/marcos-stole-another-soldiers-war-story-in-bessang-pass/

https://kami.com.ph/41567-marcos-hero-bessang-pass-steal-war-veteran-victory.html#41567

https://newslab.philstar.com/31-years-of-amnesia/war-hero