Forgotten Filipino Warriors

of Freedom

by Conrado (Sluggo) Rigor, Jr. / Filipino-American

Bulletin, Seattle, WA.

The Forgotten Heroes

Artist: Ronald Recaido

The recent awarding of the

U.S. Congressional Medal of Honor to Filipino WWII veterans has been hailed far

and wide. Seven decades later, accolades in the form of replicated medals are

given posthumously to families of thousands. The surviving few still participate

in ceremonies but are no longer lucid nor aware what the rituals are about. As a

veteran’s son, I am often invited to events honoring families of the departed

and a few still-living WWII veterans. It is heartbreaking to witness such

ceremonies. Solemn and profound with eloquent speeches by dignitaries, the

programs make sure there is hardly a dry eye when the roll calls start and the

bugle plays. Awed by the salutes and splendor, the audience remember the

warriors of freedom who are no longer around. To see once-proud soldiers on

stage---surviving well into their 90s, each one on a wheelchair, no longer able

to understand, hear nor appreciate the ceremony extolling them is in itself an

emotional experience.

**

The senior center where I work is a virtual

repository of WWII veterans’ files especially those who had come to the U.S. to

become citizens. Since the 1990s, Filipino WWII veterans of varied stripes who

chose to settle down in the Northwest gravitated towards the senior center in

Seattle. Many fought in the Pacific War as servicemen in the Philippine

Commonwealth Army, as recognized civilian guerillas, or as Philippine Scouts.

When the International Drop-In Center (IDIC) invited the old soldiers in 2004 to

relocate their small table to IDIC’s Beacon Hill office, they had by then

organized themselves as the Filipino War Veterans of Washington (FWVW). The

Commander at that time was an Ilocano guerillero, Julio Joaquin. Working closely

with Manong Julio, IDIC offered the group a room to be their official

headquarters, an offer approved by the IDIC Board which the old soldiers happily

accepted. I helped design their white gala uniform, designed their overseas cap,

designed and produced the FWVW officers’ business cards. As adviser to the FWVW,

I interviewed each one and learned about their sad plight. Thousands had arrived

in the U.S. alone because Uncle Sam had legislated that only the Filipino

veteran could come if he wished to be a citizen. They had believed that they

would also receive long-awaited WWII service pensions. In 1990 then President

George H. Bush had signed an Executive Order allowing WWII Filipino soldiers to

come to the U.S. to swear allegiance as citizens. Majority of those who came

were mostly economically-challenged ex-guerillas and enlisted men. There was

hardly anyone with a rank higher than a lieutenant. (Another intriguing account

explained by higher-ranking Filipino veterans.) Already in their mid and early

70s, many were culture-shocked, coming mainly from provincial parts of the

Philippines. Worst of all, majority were unemployable due to age and lack of

local experience. So IDIC had to arrange for them to receive SSI (supplemental

security income), a monthly subsidy enough for an unemployed senior citizen to

survive. In order for them to petition their wives and children, the veterans

had to prove that they had income. Again it was IDIC that referred them to

menial jobs to comply with immigration laws that will allow petitions to be

filed. It was heartbreaking to see old, frail warriors working in sweat shops as

janitors, laundry aides, dishwashers, kitchen aides, sharing tiny rooms at the

International District and scrimping on rent and food. Of course they were hurt

and angry but could not complain. Many shed tears and shared their agony with

us. To be able to save a little to send to their families back home and to

officially record them as employed and therefore eligible to file petitions, the

aging WWII warriors felt that their dignity was trampled upon and that no one

cared.

**

Beginning in 2005 IDIC (www.idicseniorcenter.org)

advocated in earnest for the old soldiers by affiliating with local and national

organizations. It turned out that their plight was duplicated in major parts of

the U.S. like San Francisco, Los Angeles and Honolulu. They had wisely chosen to

stay in warmer regions. In Seattle, the FWVW had 300 active members in the

beginning. Aside from veterans living in the Bush Hotel and subsidized apartment

facilities in Chinatown, others lived in King, Pierce and Kitsap counties. To

get to know them better, IDIC conducted a survey focusing on their most critical

needs. The result was heart-rending. As expected, all wanted their families to

join them in the U.S. Based on the unprecedented survey that was conducted in

Western Washington by virtue of a one-time grant from Governor Christine

Gregoire, official endorsements came from the Washington State Veterans Affairs

Office (VAO) and the Olympia-based Council of Asian Pacific American Affairs

(CAPAA). IDIC worked closely with then CAPAA Chair Ellen Abellera who made the

veterans’ plight a single-minded focus. It was the first time that a community

group would help make known the foremost desire of aging Filipino soldiers who

lived alone in America. Although there was then a high-profile national campaign

led by Washington DC-based Eric Lachica’s American Coalition for Filipino

Veterans (ACFV) and the National Federation of Filipino-American Associations

(NaFFAA) of the late Alex Esclamado to seek pension benefits for Filipino WWII

veterans as de facto wartime recruits of the U.S. Army, the old soldiers still

loudly voiced their preference for their families to join them in the U.S. At

that conference in Washington DC, there emerged a heated argument whether family

reunification should be given equal push like that of the pension issue. I

remember that the majority of veterans under Eric Lachica’s ACFV almost walked

out of the Embassy after they were turned down. If not for PH Ambassador Jose

Gaa’s appeal, the old soldiers---who really wanted their families more than the

much-delayed pension bill---would have jeopardized the conference. Unbeknownst

to the public, it was the FWVW’s and IDIC’s strategic leadership that launched

what became known (and still actively pursued) as the Filipino WWII Veterans’

Family Reunification Program. Current FWVW Commander Greg Garcia is officially

credited for the initiative and consequent recognition by Filipino veterans’

groups all over the U.S. It was Manong Greg’s position paper, prepared with the

help of IDIC, that was roundly applauded by veterans, their widows and children

in Honolulu during a NaFFAA national conference. A few months later Commanders

Montero and Garcia, with their spouses, attended a command conference in

Washington DC organized by the Philippine Embassy and the National Federation of

Filipino-American Associations (NaFFAA) to address the pending veterans’ pension

bill. I was privileged to be part of the delegation. That historic conference of

aging Filipino soldiers living in the U.S. was highlighted by meetings with the

late U.S. Senators Daniel Inouye and Daniel Akaka. And there was the

unforgettable five-minute testimony delivered by Filipino WWII hero of the Nueva

Ecija Great Raid, Lt. Benito Valdez, before the U.S. Congressional Veterans’

Affairs Committee in Washington DC. In a trembling voice and holding back tears,

Manong Benito appealed for family reunification before a hushed audience. After

that emotional speech, U.S. Senator Patty Murray, a member of the Committee, was

so touched that she stepped down from her chair to embrace Manong Benito. She

declared how proud she was that a war hero from her home State was performing

one more heroic act on behalf of his aging comrades. Two years later the lady

Senator was instrumental in arranging for the children and grandchildren of

Manong Benito---who was then on his deathbed---to come to the U.S. just in time

before he died at age 91.

**

Today, the promised reunification of veterans’

families is bogged down in bureaucratic maze. Scores of poor aging soldiers,

sickly and invalid Filipino-Americans, still wait for their children, many

granted temporary status as virtual visitors. The best that Uncle Sam could do

for Filipino WWII veterans was to award them a one-time lump sum pension

(conveniently timed with the Obama stimulus drive to jumpstart a lethargic

economy). And given only to those who are still living. Those who have died

waiting, even if they are listed in official rosters in U.S. military archives,

their widows and families do not get anything! To address the family issue,

petitioned families waiting for visa numbers are selectively given what is known

as a parole agreement. Parole visas, renewed every three years and issued by the

U.S. INS are very limiting because the aging veterans’ children can come to the

U.S. but are not allowed to hold permanent jobs. They must wait until their visa

numbers come up before qualifying for a green card that signifies permanent

residence. Which could take another decade! Meanwhile, if their fathers should

die while waiting, the petition could be annulled. What a deal! The situation

calls for an advocate in the U.S. Government to pick up the cudgels once again

for the remaining forgotten and aging warriors. It is a situation that is not

known to the general public, both in the U.S. and in the Philippines. Amidst all

of the glorious medal-awarding ceremonies, we hope that the old soldiers’

supporters can take another serious look at this sad and ironic situation.

**

U.S.-based Filipino WWII advocacy groups like the

FilVetREP are doing an admirable job at drawing attention on heretofore unknown

fragments in the continuing saga of the forgotten warriors. When the glorious

medal-awarding ceremonies are over, the next sequel will be an educational

program to perpetuate the sacrifices and valor of the Filipino soldier in WWII.

Among the supportive organizations that are proposing to fund a Professorial

Chair in the University of the Philippines’ Department of History is the Beta

Sigma Fraternity of the Pacific Northwest. Fraternity officers have met with

Prof. Rico Jose in Diliman, Quezon City to propose an academic research and

Professorial Chair to study the role of Filipino soldiers in helping win the

Pacific War. Because that part of our history is a personal matter to me and my

siblings, I have long immersed myself in research and advocacy work even before

I migrated to the U.S. All gone now---my father, my father-in-law, two of my

mother’s brothers, and three other close uncles---were soldiers who fought in

WWII. In my youth, growing up in the old Camp Murphy and then at historic Ft.

William McKinley in Taguig with fellow-Army brats (children of Philippine

military officers), I had been a member of the Sons & Daughters of the Defenders

of Bataan and Corregidor (DBC) which was envisioned by General Dionisio Ojeda to

be a generation of caretakers of our fathers’ legacies.

**

My father’s comrades had shared awesome tales about

the war and lamented how pitifully lacking post-war records are in mentioning

the role of the Filipino soldier in crucial encounters and bloody battles

against the enemy. They were disappointed to discover that After-Battle Reports

on military operations in the Philippine archipelago were based mainly on

American records, viewpoints and writings. There were hardly any wartime reports

from Filipino sources. It was explained that the country was under the Japanese

for three long years and most operations were conducted underground. It was

foolish, they reasoned, to have maintained any paperwork in that situation.

Other Filipino officers held the view that WWII happened at a time when racial

prejudice was raging in the U.S. and Filipino soldiers were condescendingly

looked upon as the Little Brown Brothers. Service records do show that Filipino

recruits in the U.S. were assigned mostly as ammo carriers, air cargo cleaners,

latrine and kitchen crews, bootblacks, battleship rust scrapers, utility and

laundry aides. Contrary to dramatized post-war tales, there were not many who

saw actual combat. In the Philippines, young soldiers in their early 20s

recruited by General MacArthur to form the Commonwealth Army bore the brunt in

defending the country from the invading Japanese. Respected Filipino military

historians and academic researchers like the University of the Philippines’

Department of History Professor Rico Jose are among those who can help establish

true accounts during WWII in the Philippines from oral and written testimonies.

There are first-hand accounts of the war in a book written by the respected

College Editors Guild (CEG) founder Ernesto Rodriguez Jr., “The Bad Guerillas of

Northern Luzon.” Or the book authored by U.S. Army Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, “We

Remained,” considered a classic tweak to another General’s “I Shall Return”

promise.

**

Generations of Filipinos and the youth in schools

must one day be able to read true accounts of how their forebears helped win the

cause of freedom in the Pacific War. Seven decades later, it should become every

Filipino’s wish to memorialize genuine accounts of that war---especially the

crucial engagements where Filipino soldiers wrapped themselves in glory and

displayed uncommon valor, thousands paying the ultimate price. Research about

brave, selfless Filipino men and women, written by Filipinos for Filipinos

should be a guiding element. Because war holds many truths, it becomes our

solemn duty as a people to be discerning, to set apart what are genuinely ours.

We must distinguish the glory claimed by others from those that rightfully

belong to Filipino patriots. #

In 1996 aging WWII veterans rallied in Olympia, seat of Washington State government, to seek help in their campaign for family reunification.

The group was led by Commanders Julio Joaquin and Amador Montero (2nd and 3rd from left). Both have passed away.

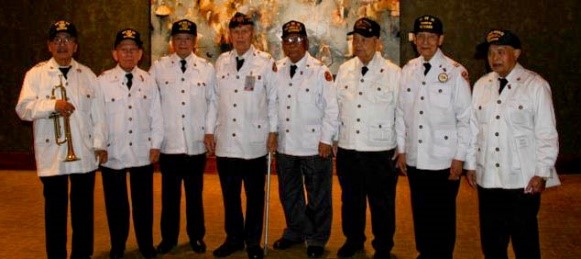

Filipino WWII Veterans of Washington (FWVW) at a

formal ceremony honoring them in Seattle.

MABUHAY KAYO !!

About the Author

Conrado N. Rigor, Jr. is executive director of a

non-profit human services organization (www.idicseniorcenter.org) based in

Seattle. Sluggo is a community journalist who also served as information attache in

Seattle’s Philippine Consulate General in the late 1980s. He is the eldest son

of a WWII veteran who had figured in the historic Battle of Bessang Pass where

General Yamashita and his invaders finally surrendered to end the Pacific War.

His email: sluggorigor@gmail.com.

About the Artist

Ronald Recaido is a Bachelor of Fine Arts graduate from California State University, Long Beach. Ron, whose father is a retired navyman, is in active service in the United States Navy. His email: recaido77@gmail.com.

Ron and Sluggo, in Seattle 2015