|

"LOLONG" - Lessons in Managing Large

Crocodiles

By: Dr. Jose Andres L.

Diaz, DVM, FPCVPH

Lolong’s life and death is a good learning experience for the enhancement

of managing our wildlife resources particularly crocodiles. In many areas

around the world where predators are found, there are instances where

these predators attack, kill and eat humans and regarded as problem

animals. Most famous of these are the man-eating lions and leopards of

Africa, tigers of India and crocodilians in many parts of the world, most

notorious of which are the Nile crocodiles of Africa and the saltwater or

estuarine crocodiles of the Indo-Pacific region. Traditionally the

accepted approach to these problem animals is hunting and killing them to

save the human populations from further harm

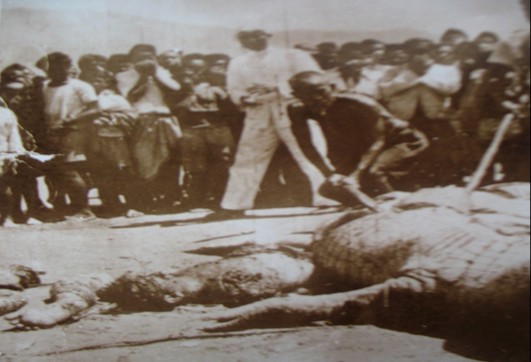

Human remains being retrieved from a man-eater croc

The celebrated hunter Jim Corbett killed many man-eating lions and

leopards and later became a famous conservationist. In the Philippines,

the famous crocodile hunter Mitsi Barsia is still regarded as a savior in

many remote areas where he killed many man-eating crocodiles. The

legendary Muslim crocodile hunters who served as a stimulus in the

settling of remote crocodile infested wetlands suitable for paddy rice

farming and aquaculture, were driven more for economic reason. The

crocodile skins are among the prized commodities in their trade to the

south eventually reaching Singapore which up to the present is the center

for crocodile skin trade in Asia. Even the current Wildlife Resources

Conservation Act of the Philippines (RA 9417) which makes it illegal to

kill and destroy wildlife exempts this in instances where there is danger

to life a limb of humans (sec 27).

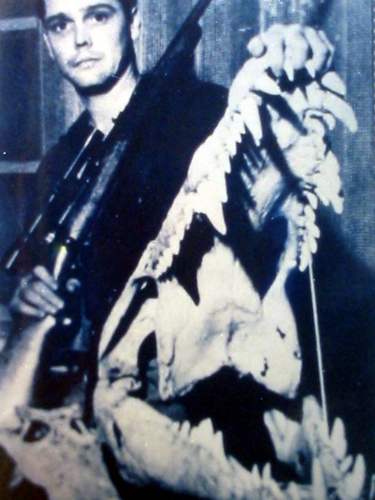

Mitsi Barsia killed thousands of crocodiles in the

1950”s to 60’s and inspired the comics series Putol.

At the start of the Palawan Project I asked him

how to get the crocodiles alive and he replied that he had no idea.

Charles Andy Ross, a herpetologist from the

Smithsonian Institution and considered the authority on crocodiles in the

Philippines. He pioneered and tirelessly promoted the conservation of

crocodiles in the country. Taken at the popular Badjao Inn, Puerto

Princesa, Palawan with Zeny Mendoza, wife of Brod Dr. Sonny Mendoza -

owners, during the heyday of crocodile trapping for the Palawan Crocodile

Institute where I served as the Founding Director.

The paradigm shift in treating crocodiles started with the establishment

of the RP-Japan Crocodile Farming Institute (or CFI) in Palawan in 1986

(now Palawan Wildlife Rescue and Conservation Center or PWRCC). The

primary aim of the institute is to remove the conflict between humans and

crocodiles by capturing alive the problem crocodiles and bring them to the

breeding facility to serve as breeders - thereby conserving the endangered

species. A gratuitous permit was issued by DENR and more than a hundred

large saltwater crocodiles (Crocodylus porosus) were captured from all

over the country and became the breeding stocks which produced the present

crocodile industry in the Philippines now numbering to more than 30,000

animals. This industry regularly supplies farmed CITES registered

saltwater crocodile skins to the famous Hermes fashion house. This effort

also involved the conservation of the endemic Philippine crocodile (Crocodylus

mindorensis) which is highly endangered and numbered only some 200

individuals now successfully bred in captivity and reintroduction to its

natural habitat is ongoing. The conservation of crocodiles is regarded as

the most successful program in conserving Philippine endangered wildlife

species.

A large former man-eater that served as breeder in the

Palawan croc farm

Third generation farmed saltwater crocodiles

In 1992, the National Integrated Protected Areas System Act was enacted.

Among the protected areas declared was the Agusan Marsh Wildlife Sanctuary

(est.1996). It aims to conserve the role of the Agusan Marsh as the catch

basin for the region, thereby managing its seasonal flooding and

conserving the many flora and fauna found therein, including the last

remaining intact crocodile habitats and large natural crocodile population

left in the country. As in many parts of the Philippines, Agusan Marsh

Wildlife Sanctuary has many human settlements in its periphery. Human

activities both indigenous and migrant have traditionally been an integral

part of the whole area where people travel, fish and collect resources.

The management of the Protected Areas has to closely integrate the

presence of the large potentially dangerous crocodiles with the inevitable

human activities. Before the Agusan Marsh’s declaration as a Protected

Area, any actual or perceived threat to humans by crocodiles is promptly

addressed by simply killing the problem crocodiles through community

effort. Nobody from the community would even inform the authorities as

everybody believes that it is the proper thing to do.

In 2009, I was requested by an old friend in crocodile conservation and

diving buddy, Sonny Dizon, to help the mayor of Bunawan, Agusan del Sur to

address the problem of man-eating crocodiles in their area. We met Mayor Elorde in Davao who needed help to kill the problem crocodiles. I advised

him to capture the animals instead and make use of it as an educational

medium and tourist attraction. He initially could not comprehend the idea of

capturing and keeping alive a huge man eating crocodile. We conducted in Bunawan (with PAWB and PWRCC staff) an orientation and training program on

the conservation of crocodiles focusing on the techniques to safely

capture, handle and manage crocodiles in captivity and demonstrated the

use of crocodile snares to the local crew who will undertake the trapping.

These snares are copies of the original from Zimbabwe which we imported

years back and successfully used in capturing alive the many crocodiles in

the Palawan farm.

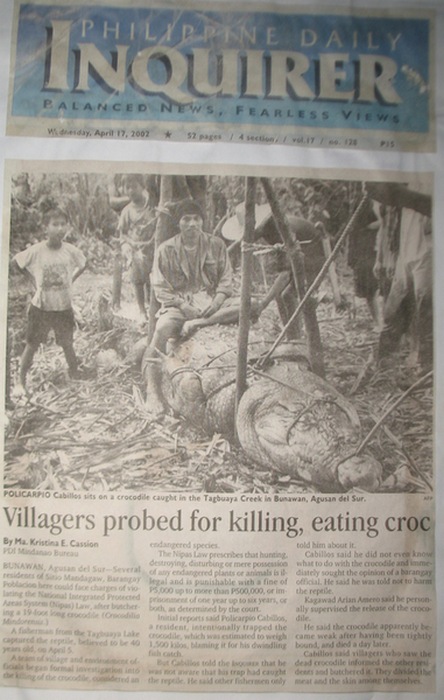

A 19 footer saltwater crocodile caught in Bunawan in

2002.The animal subsequently died and the meat eaten by the locals as

traditionally done. The lack of definite policy and program on how to

manage large man-eaters will end up with casualties on both sides and

worsen the relationship between humans and crocodiles.

Orientation and training on the conservation including

capture techniques and captive management

of crocodiles held in Bunawan. The participants

eventually captured and managed Lolong.

I also advised them to acquire the proper permits from the DENR and ensure

that the facility to keep the crocodile must be ready before they even

start the trapping. The facility must conform to a design suitable for

large wild caught crocodile and nearest to the habitat to reduce stress of

handling and transport. I emphasized that the common experience in

Australia, which has the best program in conserving salt water crocodiles

and our model, is the death of huge wild caught crocodiles due to stress

of capture, handling and transport over long distance. These mortalities

occur a few days after capture and later found out to be due to the

accumulation of lactic acid in the muscles as a result of anaerobic

exertion due to prolonged handling and transport. We learned this lesson

in our years of catching large crocodiles and while we had a few

mortalities, most wild caught large crocodiles eventually became breeders.

Lolong is one of the few large crocodiles left in the

country and became popular because it was captured alive.

The others were simply killed by the locals ,hidden

and simply ignored by the authorities and conveniently forgotten.

It took some time for the DENR to issue a permit to catch the problem

crocodile and a team from PWRCC was dispatched to the area accompanied by

the locals. Unfortunately, a member of the PWRCC team - Lolong Conate - died

and when his remains was brought to Palawan; the locals continued the

trapping and caught a big crocodile. The crocodile was named Lolong in

honor of the trapper and turned out to be the biggest in the world. This

transformed Bunawan from an unknown, remote 5th class town into celebrity

status. Immediately there was a chorus of attention grabbing circus

ranging from animal rights clamor to release the animal or to bringing

the crocodile to Manila. The Bunawan facility was recognized by the

authorities, regularly monitored, extended technical support and became a

big tourist attraction. The latter brought big income and prestige to the

community.

Visit to Lolong as part of continuous support

to manage the largest crocodile in the world.

The facility is far better than the usual

crocodile pen with dedicated staff and tight security including 24 hour

camera monitors.

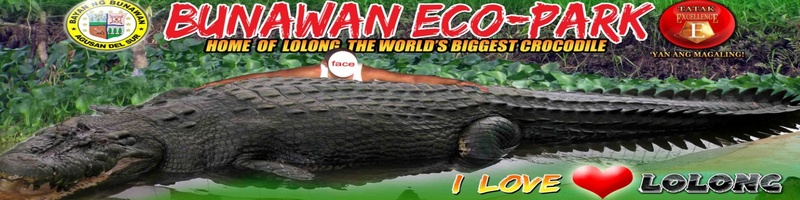

In our visit to Lolong in 2012, we observed that the facility needs proper

signages to attract more attention and bring in more visitors. It is good

that the Mayor immediately agreed to partner with Dr. Ayong Lorenzo, owner

of Excellence Poultry and Livestock Corp and El Dia Crocodile Farm as part

of his corporate social responsibility to promote the conservation of

crocodiles. Immediately, signages were established in the main highway of

Agusan and in the road towards the crocodile facility, greatly increasing

the number of visitors.

After successfully managing Lolong in captivity for one and a half years,

the biggest crocodile in the world died. Again, there was a chorus of

condemnation and finger pointing as to the culprit in the whole episode.

The authorities conducted a necropsy and declared that the cause of death

is ‘’chronic pneumonia complicated by multiple organ failure’’ (Phil Star,

March 3, 2013).

Signages to promote Lolong which brought mixed

results. Many appreciated the effort and

brought prosperity and fame to the

remote town. Others criticized it to gain media attention .

Some lessons learned:

1. What is our policy regarding problem crocodiles?

If we conserve crocodiles in the wild, inevitably we will have problem

crocodiles. Small crocodiles will one day become big, aggressive and take

bigger prey to satisfy their bigger appetites and end up to eating people.

Protected areas cannot be off limits to people especially in the

Philippines with exploding population and poor law enforcement. People

will inevitably end up as crocodile prey when they enter crocodile habitat

where problem crocodiles rule.

Big old crocodiles hold large territories and they would kill and devour

interlopers inside their territories whether it is a smaller crocodile or

a human being. According to Australian Dr Graham Webb, the world’s

foremost authority on salt water crocodiles, the biggest threat to other

crocodiles in a natural population is an old big dominant crocodile (that

is aside from humans). It will kill and devour the smaller ones in its

territory. This coupled with the danger to humans as recognized in the

wildlife law of the Philippines (that is instead of allowing the killing

of crocodiles attacking humans) is enough reason to address the concern on

problem crocodile by removing and keeping them in a safe facility. This

approach is an integral component in the successful management of

crocodilians in many parts of the world.

At the time when Lolong is celebrated as the world’s largest, there has

been a clamor by the people of Bunawan to be allowed to capture another

large man eater in the area as it has been attacking livestock after

devouring a local inhabitant. The request has been ignored as the debate

on what to do with Lolong (alive and dead) is ongoing.

The Agusan Marsh Wildlife Sanctuary gives priority in managing the natural

population of crocodiles in the area. It must also prioritize the proper

relationship between the crocodiles and the inhabitants that are affected

- either as living around or inside and doing activities inside.

The Agusan Marsh Wildlife Sanctuary under the DENR has an office in

Bunawan but only the LGU has a facility to maintain large captive

crocodiles. The management of the AMWS has to recognize the role of that

facility in managing the crocodiles therein.

With Dr Graham Webb and Brod Dr Ayong Lorenzo during

the Crocodile Specialist Group meeting held at the National Museum of the

Philippines. The El Dia Crocodile Farm we established maintains both

Philippine crocodile and saltwater crocodile. It is among the few

facilities that successfully bred in captivity the endemic and highly

endangered Philippine crocodile.

2. What really killed Lolong?

Was it swallowing a length of rope as earlier reported? Was it the

rumored deliberate poisoning to embarrass the mayor who is running in the

next election? Was it due to stress and mismanagement due to the greed in

bringing in more tourist and money as repeatedly harped on? Was it a case

of chronic fungal infection of the lungs which made Lolong "not feeling

well even before his capture and taking Lolong from its natural habitat to

its new home made its condition worse’’, this fungal infection made

breathing difficult, affected its heart, leading to congestive heart

failure and death? (Phil Star, Mar 3, 2013)

The necropsy conducted by veterinarians from PAWB, PWRCC and Davao

Crocodile Park did not see any rope. They also did not conduct a

toxicological examination.

Sample tissues, however were collected and sent to UPLB College of

Veterinary Medicine for histological pathological examination. The result

of the UPLBCVM examination is chronic respiratory disease due to fungal

infection.

Philippine authorities state that Lolong’s age is estimated to be between

50 and 60 years old. Some say that crocodiles live up to a hundred years.

There is no reliable way of determining the age of a crocodile especially

from the wild. The only way to reliably know a crocodile’s age is to keep

a record from day one.

In the book Eyelids of Morning by Alistair Graham and Peter Beard, my

treasure from the visit to the Smithsonian Museum as recommended by my old

buddy and mentor croc expert Andy Ross, the authors made a survey of

crocodilians the age of which were reliably recorded and found out that

the greatest age recorded by any zoo for any species of crocodilian is

less than 60 years.

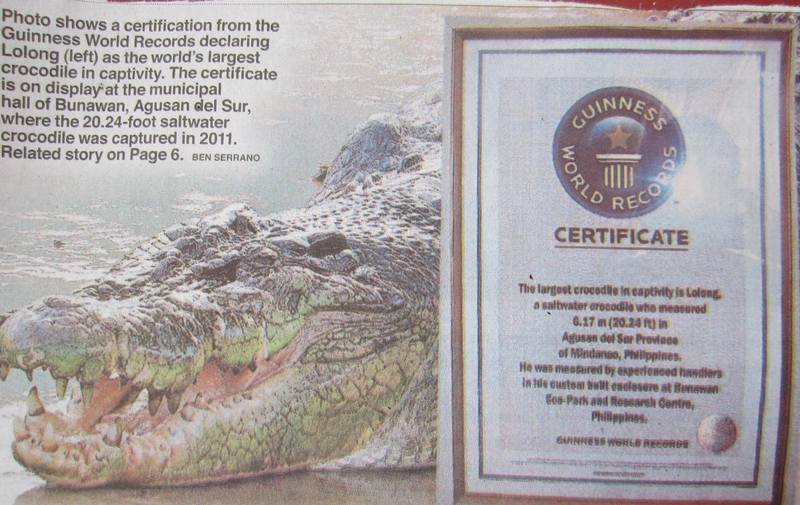

Lolong measures 20.24 feet and weighs 1000kg - the longest/largest in the

world as confirmed by the Guinness world record.

The same book “Eyelids of Morning ”which according to the Chicago Tribune

is “probably the best book ever written about crocodiles”, retells the

account of the biggest crocodile ever .

In 1825,a Frenchman, Paul de la Geroniere who lived in Luzon, Philippines

was greatly annoyed by a crocodile that killed and ate one of his horses.

Assembling a posse of spearmen, he led a chaotic tallyho after the croc,

which because of its bulk and the smallness of the river, was unable to

escape. Nevertheless, six hours and uncounted spear thrusts later it was

still alive. La Gironiere had fired several shots from close range, once

into the reptile’s mouth, seemingly without effect. In fact he later found

that his musket caused scarcely any injury. Then a resourceful hunter

drove a lance into the animal’s back with a hammer and by a fluke found

the spinal cord and killed the croc.

The beast was so heavy it took all 40 hunters to roll it ashore. ”When at

last we had got him completely out of the water we stood stupefied with

astonishment .From the extremity of its nostrils to the tip of its tail,

he was found to be 27 feet long, and his circumference was 11 feet,

measured under the armpits. His belly was much more voluminous ,but we

thought it unnecessary to measure him there ,judging that that the horse

that he had breakfasted must considerably have increased his bulk…”

La Geroniere was so impressed by his prize that he carefully prepared the

skull and sent it to the Agassiz Museum at Harvard. Nearly a century

later, in 1924, Thomas Barbour, the herpetologist searched the Agassiz

Museum for La Gironiere’s croc. Sure enough he found an enormous skull,

unfortunately unlabelled, but of an estuarine croc with a palate injury

corresponding to La Gironiere’s musket shot. It is highly likely that this

the one from Luzon; but if it is, then La Gironiere’s tale (written 29

years after killing the croc) is tainted a little with fabulous tradition,

for the skull measures a fraction less than 36 inches. Since the length of

a croc’s head is not more than one-seventh of total length, it is easy to

calculate that the croc was only 21 feet long not 27. Nevertheless ,this

is still the ”all-time world-record” croc. The difficulty the hunters had

rolling it out of the river is not surprising, for a 21 footer would weigh

1.25 tons.”

If Lolong is 50 years old and expected to live up to 100 years, what would

be its maximum size at that age? Could it be possible that given Lolong’s

maximum size and weight, it has also reached its maximum age.

If the reason for the death is stress, crocodiles have evolved to live a

very stressful and violent life. They have survived from the age of

dinosaurs. They are apex predators that hunt and attack large dangerous

prey and thrive on diseased rotting carcasses in the wild. In fact the

current research is focused on utilizing crocodile serum to treat a

variety of infections including HIV, proving that crocodiles can resist

many diseases that can kill other animals. Crocodiles survive and thrive

in captive conditions that could otherwise kill other creatures.

Or maybe Lolong has reached its life’s end, being too old, lost its super

resistance and therefore bound to die?

In managing wildlife in captivity, the inevitability of death especially

of old animals is an accepted fact.

3. What do we do when something like Lolong dies?

Recognizing the inevitable death of an old valuable specimen, there must

be a program to handle its remains as soon as the animal dies.

Arrangements must be done in advance how to immediately manage the carcass

so as to prevent deterioration. Identification and coordination with

experts who will do the necropsy and taxidermy should be done in advance.

The necropsy team should be accompanied by the taxidermy team to ensure

that the proper cuts would eventually produce both necropsy findings and

proper preservation of the remains. Valuable parts and specimens that

should be preserved for different reasons, if only for posterity should be

systematically done.

Lolong is the biggest crocodile in the world and given the expanding

crocodile farming industry in the country it could have been a good

opportunity to preserve its genetics - both somatic and reproductive

tissues from the testicles with sperm cells to serve as future source of

genetically important materials. Saltwater crocodiles are the largest of

the extant reptiles .Their skin is the most prized and most expensive of

all crocodilians. The two largest specimens recorded come from the

Philippines. The Philippine saltwater crocodile populations could have the

unique genetics to produce the largest in the world and very valuable in

improving the genetics of farmed crocodiles. The serum, and other organs

alike, the heart, penis, eyes, etc. and even the gastroliths are valuable

natural heritage of once was the biggest crocodile in the world.

I was informed that the skin was salted and stored waiting for

bureaucratic decision and that the bones would be eventually dug up after

the skinless carcass was buried to decompose.

Maybe, that is the tragedy of Lolong. It was looked upon as another

crocodile that at best will eventually be preserved for tourists. Its

value as a unique specimen and a national natural treasure seems to have

been lost.

However, all is not lost if we learn from this incident and apply it to

the better management of our precious wildlife species. Then the death of

Lolong would not have been in vain.

(Back --->

Environmental Awareness)

(Back ---> Current Features)

|